Field Guide to the Ordinary Buildings of Manhattan

INTRODUCTION

E.V. Haughwout Building, 488-492 Broadway. Photo by Kenneth C. Zirkel

Conversely and complementary to all that, the purpose of this architectural guide is to categorize and describe the ordinary buildings of Manhattan, the dominant constituents of its architectural fabric. Conventional architectural guides, including the AIA Guide, do not ignore ordinary buildings, but they generally discuss them as individual buildings that have some outstanding, graceful, pleasing or unusual feature that has captured the attention of an observer acting as architectural critic. This is entirely appropriate, of course, but it leaves the greatest part of New York’s built environment, that which surrounds us and defines the physical space of the city, pretty much out of the discussion and intellectually invisible

There are many architectural guides to New York City and Manhattan; the best known is surely the AIA Guide by Norville White and Elliot Willensky. All of them share the same basic orientation, which is to identify and describe the important architecture of New York City as expressed by individual buildings (such as the Flatiron Building and St. Patrick’s Cathedral) or complexes of buildings (such as Rockefeller Center and Tudor City).

Except for the occasional oddity or curiosity, every building discussed in the AIA Guide is included because of its superior architectural quality (Haughwout Building in SoHo), its size or prominence (CitySpire in Midtown North), its historical significance (2 White Street in TriBeCa) or the importance of the role it plays in the life of the city (Port Authority Bus Terminal in Midtown South).

2 White St. Photo by Beyond My Ken, CC BY-SA 4.0, Via Wikimedia Commons

This guide is not architectural history or an academic study but primarily a product of observation, an effort to account for what is visible, an effort that requires considering every building on every street to be equally interesting, at least in a sense. Our eyes tend to sweep past drab, muddled, incoherent objects and spaces, hardly registering their contents. But the bulk of Manhattan’s built environment is functional, minimally maintained, inarticulate or some combination of all of these. The charming lane in Greenwich Village, a street wall of massive prewar apartment houses on Central Park West, gleaming, edgy development along the High Line or Hudson Yards–such visually impressive and coherent scenes are actually a small part of the total we must consider to account for the existing built content of the city.

“absences… as important as presences in shaping the character of an urban space”

Every building comes to us from a particular moment, with a specific program, a program that then usually evolves, causing observable changes in that building’s outward appearance. Every street of Manhattan is occupied by its particular set of material facts (principally buildings but also pavement, fences, trees, etc.) accumulated over decades or centuries. As these elements accumulate, they are sometimes discarded, often leaving gaps and voids, absences that are as important as presences in shaping the character of an urban space. We can’t hope to understand ordinary buildings and how they combine to create the fabric of the city if we see things through the lens of architectural criticism, ignoring incoherence as we search for beacons of beauty and excellence.

In fact, it turns out that neither architectural histories nor specialized studies of urban architecture nor books about New York are as helpful as one might expect for learning about its ordinary buildings or the processes that shaped its architectural fabric. There is a lot written about important architects and skyscrapers, brownstones, Art Deco and the housing reform movement. Virtually nothing has been published about low- or mid-rise 20th century commercial buildings, postwar apartment buildings or subsidized housing modes of the 70s and 80s. An architectural reference history of New York City that one can appeal to for general answers about ordinary buildings doesn’t seem to exist. Always, the focus is on particular buildings, notable buildings and particular, notable designers.

Really, the only way to find answers about ordinary buildings is to look at them, thousands of them, all kinds large and small, in every situation, in every neighborhood and district, look for patterns and exceptions to patterns, and try to account for the facts of their appearance. It is really only possible to study many thousands of buildings and to identify and test the significant patterns that emerge from doing this because Google Street View exists. The same is true to a lesser extent for Google Satellite View, which allows an observer to see the entire footprints of individual buildings and the massed buildings of whole districts . These marvelous tools enable an observer to leap from block to block, from neighborhood to neighborhood, continually refining provisional insights that might help in accurately describing the architectural fabric. The other major tools used to gather essential facts for this study are the NYC Department of Buildings database and the NYC Department of Landmark Preservation database. Also essential is the NYC Public Library’s collection of historical “fire insurance” maps, which offer fantastic views of the Manhattan’s architectural fabric at different points of development, with much key information about every building that existed at a particular time. These maps create a kind of choppy animation of the city’s development, showing the filling-in of urbanizing sections, the replacement of parts of one layer with additions from the next layer.

“A neoclassical keystone lintel immediately identifies the 20th century ‘Aughts’ as the decade of its construction” on 447 W. 160th St.

Through observation and research, thousands of buildings must be interrogated individually: When was it built? When was it altered or modernized? What was it built to do and how might that function have changed over time? And hundreds of blocks in every section of Manhattan must be observed and interrogated: What types of buildings, which layers of development are represented on a given block in a given neighborhood? What is the function of a neighborhood at present and how many changes of function are represented in its current architectural fabric? And on and on with these questions. A very long process of observation and research generated all of the generalizations described in the guide and the names labeling them, including its historical scheme of eras and periods, the categorization scheme of fabric building types, and, in a few cases, names for styles that need names but didn’t seem to have them.[1]

The aim of the NYTW Guide to Ordinary Buildings of Manhattan is to enable any observer to make sense of what is inarguably one of the most complex and dense built environments in the world. Its goal is to provide a framework for understanding virtually any building of Manhattan’s cityscape: 1) when it was built; 2) what function it was intended to perform; 3) what other elements present at the time of its construction are still present; 4) its essential type among a taxonomy of types; 5) what is that type’s distribution and importance is in the context of the whole city; 6) what visible characteristics and features of a particular building can tell us about its identity and how they may have evolved since initial construction. In short, the guide is a tool for “reading” the buildings of Manhattan and the fabric of the streetscapes and larger cityscapes they comprise.

Projecting cornices of the 1910s at 100 Hudson St.

Every visible feature of a building is a signifier that, together with other details and various levels of context, locates it at a specific moment in the dynamic evolution of New York City’s built environment.

Rhombus design typical of the 1910s-1920s at 16 Arden St.

A neoclassical keystone lintel immediately identifies the 20th century “Aughts” as the decade of its construction; a decorative rhombus reliably indicates the years 1915-1925, when it was a powerful talisman of modernity; a massively broad projecting cornice almost always represents the Premodern Period of Manhattan architecture (1901-1916); pink granite represented “classiness” for architects and corporate clients of the 1980s; glazed white brick (in combination with setback penthouses) nearly always signifies an apartment building of the early 60s. These signifiers were intentional messages from builders to their contemporaries and, occasionally, posterity as well. Almost always, a large part of this message is simply that a building is of its moment, a declaration often accomplished merely by including a few trendy elements that set it apart from a similar building made a few years before. This is the part of the evolution of design that is purely fashion.

What we mean by the terms “ordinary building” and “fabric architecture” requires some explanation. It is tempting to use the familiar term, “vernacular”, rather than the less familiar term “fabric”, for the kinds of ordinary architecture we are considering here, and it would not be entirely wrong to do so. But vernacular building, in its original sense, involves the use of designs, materials and techniques of a “traditional” society, and that meaning barely applies to much of New York’s architectural development. “Ordinary” and “fabric”, as they are used here, refer to well-defined types of buildings erected in large numbers to serve specific functions. The function of housing 19th century immigration was performed by Victorian Prelaw and Old Law Tenements; housing provided for low-income populations after tracts of Prelaw and Old Law Tenements were removed by “slum clearance” were Postwar Superblock Complexes; the necessary commercial and industrial structures for a city in transition to an industrial economy were Premodern Early Steel-Frame Buildings (all these bolded names of fabric building types are described individually in the body of the guide).

From this perspective, even icons like the Chrysler Building and the Dakota Apartments are fabric buildings—this term is not meant to imply mediocrity or anonymity, only that a building can be classified with similar buildings to form a basic type, a fundamental constituent of the architecture of the City. Of course, most individual fabric buildings of Manhattan are routine and unremarkable, but the universally acknowledged beauty of Manhattan’s architecture is hardly the sum of its masterpieces.

1960s white brick at 21 East 68th St.

1980s pink granite at 415 East 37th St.

It is, rather, the product of the density and energy of its ordinary buildings and their often heedless juxtapositions as organized by Manhattan’s rectilinear grid of streets. The special excitement of Manhattan’s cityscape often arises from the tension between the extreme coherence of its grid and the radical discontinuity of its architectural fabric.

Implicitly, fabric buildings are defined in contrast to what we call “Network Buildings”, structures erected to fill specialized, institutional needs: synagogues, courthouses, schools, museums, police precinct headquarters, hospitals, college campuses, libraries. Such buildings are essential components of a cityscape but they are consciously designed to stand apart from its common fabric. Their sponsors (government, churches, charities, utilities) construct NBs to further programs that are regional or even national in scope, and Network Buildings often have very little direct relation to other development in the communities in which they are placed. Of course, most churches, public schools and firehouses are meant to serve needs in their immediate vicinities but they are components of networks that are distributed over many localities, and their design always expresses this structural difference. Interestingly, “storefront churches”, the sort that occupy spaces in older buildings or converted theaters or supermarkets in low-income neighborhoods, are just another type of local commercial tenant. They are distinguished from regular denominational churches by their lack of belonging to a wider network. A handful of other network buildings are genuine singularities more than individual representatives of institutional networks; the Guggenheim Museum certainly is one of these.

The Guggenheim Museum at 1071 5th Ave. While a lovely piece of architecture, this Network Building does not reflect the ‘fabric’ of a neighborhood. Ajay Suresh from New York, NY, USA, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

All construction in Manhattan that contributes to its existing fabric can be assigned to one of four major eras: Victorian (1835-1901), Urban (1901-1942), Postwar (1947-2000), Current (2000-present). Each of these Eras is divided into two Periods, with the exception of the Current Era. The complete name of each of the basic types of Manhattan fabric buildings described in this guide begins with its period label: Early Victorian (1835—1875) , Late Victorian (1875—1901), Premodern (1901—1916), Prewar (or Interwar) (1916—1942), Postwar (1947—1975), Postmodern (or Late Postwar) (1975—2000), and Current (or Design) Era (2000—present).

Sylvan Terrace is the last surviving row of wood-frame houses from the 19th century.

Manhattan’s earliest layers and their characteristic types of fabric buildings are completely extinct. For example, no 18th or 19th century streetscape of wood-frame dwellings has survived to the present, with the single exception of Sylvan Terrace (1882). In fact, not even one individual fabric building from the city’s first 150 years exists, even in isolation, and only one network building comes to us from the city that witnessed the American Revolution (St. Paul’s Chapel, 1768). For our purposes, vernacular architecture of the 17th and 18th centuries is irrelevant, an abstraction as remote as the woodlands that once grew and streams that flowed on uncolonized Manhattan.[2]

There remains in Lower Manhattan, of course, the trace of an early layer of fabric that precedes 1835, perhaps several hundred buildings in all. In a way, this category of Federal Dwellings could be placed into a discussion of Early Victorian types, largely because of 19th century alterations that essentially converted the great majority of them into a type of Early Brownstones. But, although these Federal Era buildings make only a very minor contribution to the architectural fabric, they provide a material link and a few vivid glimpses of Manhattan’s cityscape as it developed prior to New York becoming the unrivaled premier city of the new republic. Federal Dwellings are included in the framework of this guide as a preface to its main body covering the four fundamental eras of development.

Alterations to these Federal Era buildings on Oliver St. make them appear like Early Brownstones.

The transition from Flemish bond to common bond bricks is a clue that 2 Oliver St. was a Federal era building modified in the late 19th century.

Each of the four basic eras of architectural fabric represents a distinct set of attitudes about building and urbanization. The transitions between eras are surprisingly dramatic, even abrupt. Three critical inflection points divide the continuous mass of Manhattan into four largely distinct cities separated by time.[3] The single most important idea of this survey is that these four eras, in seven periods, form the best framework for placing every building of New York City in its essential architectural context.

The most important skill we could impart to our reader is the ability to identify, most of the time, solely from visible cues, any building’s era of origin. Each era, each period and, in some instances, even a particular couple of years, presents characteristic arrays of features that can establish the date of construction of a given building: the size, color, texture and pattern of its bricks, the size, spacing and framing of its windows, the symbols, motifs and images represented in its ornamentation. The degree of success of this guide can be measured by the accuracy of its users’ guesses at the dates of construction of the houses, tenements, apartment houses and skyscrapers that surround them as they walk the streets of Manhattan. Of course, some buildings are tricky, almost always due to modernizations and makeovers but, in many cases, it’s possible, with a little luck, to actually nail the year a particular building was constructed solely by its appearance.

Independence Plaza, a postmodern complex at 40 Harrison St. in TriBeCa

The Western Union Building is a Prewar Set Back at 60 Hudson St. in TriBeCa. Beyond My Ken, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Materially, all Manhattan neighborhoods and, perhaps, most blocks are aggregations of architectural layers from more than one period or era. For example, TriBeCa combines primarily Early and Late Victorian Loft Buildings and Current Era Design Multiple-Dwellings, with significant contributions of Premodern Steel-Frame Buildings, Prewar Setback Buildings and one major Postmodern Complex (Independence Plaza). Also represented in this neighborhood are a cluster of Early Victorian Brownstones (which are actually Federal Dwellings), a cluster of Postmodern Apartment Buildings, several Postwar Modern Buildings, one Postmodern Tower and one Current Era Residential/Commercial Tower. TriBeCa’s rough parity of layers from seven periods is unusual for a smallish Manhattan neighborhood.

Most neighborhoods languished through one or several of the seven periods of development laid out in this framework. In addition to TriBeCa only a few neighborhoods (Greenwich Village, Gramercy and Turtle Bay, among them) combine significant development from all four basic eras. In some areas, one type of architectural fabric from one period is dominant, resulting in a sort of architectural monoculture. The Fort George section of Washington Heights is a near Brigadoon of Premodern New Law Tenements from the early years of the 20th century; they represent the first layer of urbanization to occupy these blocks and very little has been added or taken away in subsequent decades. The same is largely true of Morningside Heights, except that its fabric is predominantly Premodern Early Apartment Houses.

Premodern New Law Tenement at 555 W. 186th St. in Fort George

Of course, some individual fabric buildings were built in isolation and many others have become isolated as their siblings were torn down and replaced by newer layers of urban fabric. Lone, one-off brownstones can be found in Washington Heights (artifacts of Carmansville) that were built long before the city expanded to envelope them. Lone brownstones can be found throughout Midtown that were once part of block-long rows of identical houses that vanished in the first decades of the 20th century. Anomalies of development of every variety and description are in evidence throughout Manhattan. Groups of thoroughly ungentrified Prelaw Tenements from the time of the Civil War endure in the Sutton Place section. In the summer of 2020, surrounded on all sides by Lower East Side public housing projects, One Manhattan Square, with its adult tree house and its sunken tranquility garden, achieved completion.

This lone brownstone on 60th St was subsumed by the larger building behind it at 750 Lexington Ave in Midtown.

Premodern Early Apartment House at 423 W. 120th St. in Morningside Heights

This brownstone at 503 161st St. is a holdover from the old hamlet of Carmansville, now Washington Heights.

Compared to Hong Kong or Manila, the architectural fabric of Manhattan is old, and it is older than the idea of Manhattan lodged in our imaginations. The lion’s share of the architectural and shared spaces we walk through in Manhattan were built by persons and for populations and functions that have all long since departed.

The glamor and spectacle of supertall buildings, the explosion of high profile development in Hudson Yards and along the High Line, the hyperbolic evolution of restaurants and retail activity—all can distract us from recognizing the profoundly artifactual character of the built city New Yorkers inhabit and tourists visit. Manhattan’s vast inventory of 19th century fabric, Brownstones, Tenements and Loft Buildings, is significantly represented in every neighborhood, with the exceptions of Inwood (at the northern tip of the island), Roosevelt Island (which is on its own island), and Battery Park City (on 20th century landfill). Seventy-five percent of the buildings in Manhattan are artifacts of one sustained explosion of construction between 1900 and 1930.

“Groups of thoroughly ungentrified Prelaw Tenements from the time of the Civil War endure in the Sutton Place section.” 1024-1032 2nd Ave.

In all the decades since 1930, the only truly large-scale alterations to the architectural fabric of Manhattan were the clearing of “slums” and their subsequent replacement by postwar superblock development. Except through urban renewal condemnation, the only cleared tracts of Manhattan available for the creation of postwar cityscapes were on landfill (Battery Park City), land opened for development by the removal or restructuring of rail yards (Hudson Yards, Riverside South) and the outlier of Roosevelt Island. The other great opportunity for making continuous postwar architectural fabric was provided by the dismantling (1938-1955) of the 2nd, 3rd, 6th and 9th Avenue elevated train lines (“els”). Els in Manhattan were typically flanked by light manufacturing and low rent housing. The departure of the 6th Avenue elevated allowed for the postwar development of a corridor of corporate headquarters between 47th and 57th Streets. The closing of the 2nd and 3rd Avenue elevated lines greatly changed the character of a string of neighborhoods from Gramercy to Yorkville, adding a layer of postwar fabric to areas that had been largely passed over in the first half of the 20th century.

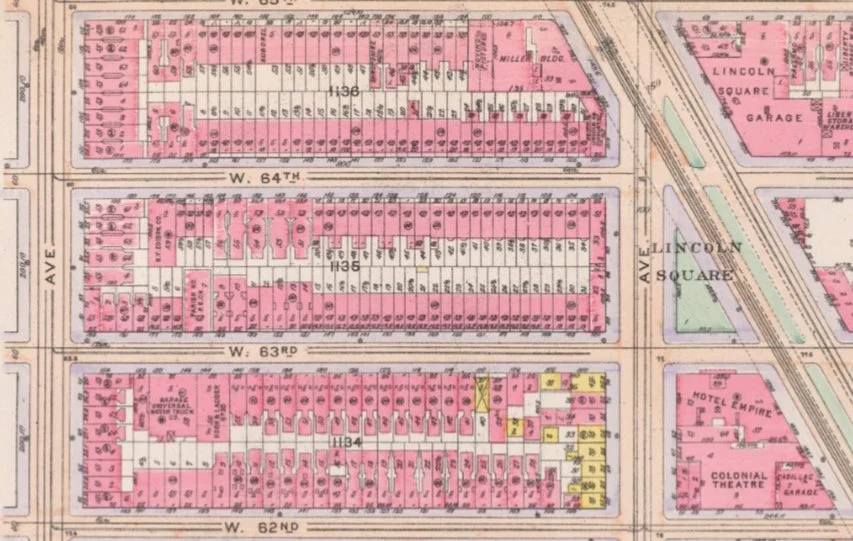

A 1916 fire insurance map shows San Juan Hill before slum clearance made way for Lincoln Center

The most important exclusion, as discussed, is Network Buildings of all sorts. Institutional buildings often have little relation to the commercial and residential buildings of their locality or that were built contemporaneously. Churches of the 19th and 20th centuries were usually intended to look, at least symbolically, centuries old. Public school architecture of different periods often little resembles commercial or residential buildings erected at the same time. No one doubts the architectural and cultural importance of the Guggenheim Museum or Lincoln Center but these works were designed to be completely alienated from the architectural vernacular that surrounds them.

Another subset of exceptions are fabric buildings that are easy to classify but belong to categories that are too rarely represented in Manhattan to belong in an accounting of its fabric architecture. There are, actually, a fair number (hundreds, at least) of wood-frame dwellings in Manhattan but nowhere do they have even a marginal impact on the essential character of an existing neighborhood or district.[4] There are some Postwar Industrial Buildings in Manhattan (Gansevoort Market Meat Center) but, again, not in numbers large enough to have a separate place in the taxonomy of this guide. The same is true of Current Era low-rise and mid-rise commercial buildings. They are not entirely absent in Manhattan but only much taller ones are sufficiently numerous and impactful to be included here as a type of fabric building, CE Commercial/Residential Towers.

Finally, modernizations, renovations, subtractions and additions greatly muddle the identity of many thousands of buildings, including a high proportion of tenements and smaller, older commercial buildings. Often, all original ornamentation is stripped from a building’s façade, its cornice is removed or “updated”, and its surface materials are covered over with stucco or some other substance, or an entirely new facade. A building may have the bones of Victorian construction under a postwar skin. Virtually every brownstone that remains in Midtown Manhattan, and there are hundreds of them, has been substantially altered in some combination of ways, often to the point of total obfuscation.

Lincoln Center

Before going into the substance of the framework, we should repeat that there are thousands of buildings that are not easy to place in its system or are clearly outside it. There are several major reasons why a particular building may not fit neatly in any of the 20 plus categories described in this field guide.

Alterations to the ground floor of 522 5th Ave disguise the building’s age

Many renovations go beyond cosmetic changes and structurally alter their interiors, adding elevators, relocating windows, adding higher floors, and the like. It sometimes becomes difficult to reasonably assign the origins of such buildings to any specific period. Beyond that, total makeovers of major office properties, particularly in Midtown North, are very common and can be quite difficult to detect, although usually there remain some telltale signs that a building is older than it is meant to look (522 5th Avenue, 1896/1960; 360 Madison Avenue, 1916/2002). The whole point of such exterior makeovers is to persuasively disguise the origins of a particular building and have it perceived as modern.[5]

This guide to the ordinary buildings of Manhattan is intended to be a reference tool for contemporary flaneurs (to put a fashionable spin on it) who want to acquire a working knowledge of their surroundings. In Manhattan, buildings surround us. To understand the cityscape, we must identify its characters as individuals and as types. Beyond this, we also think of the guide as a kind of architectural game that can be played solitaire or competitively. How old is that building? Which details of its appearance betray its origins? Can you place it within five years of its creation?

We hope you continue to read our guide and glean from it a new perspective of our fair city.

End Notes:

1. For the sake of clarity, we should note that some of the terms, categories and concepts used in this guide have definitions that are peculiar to it. Of course, many of them are standard terms and concepts; we haven’t invented “brownstones” or “prewar” or “International Style” or “Loft Building”. But we use “Loft Building” as a label for more buildings than actually have large, open factory lofts, and apply the term to any kind of dedicated, 19th-century commercial building, including fancy showroom buildings in the Ladies’ Mile and office buildings organized for white collar work. Also, the guide’s basic historical framework of four Eras and seven Periods, and the labels we use to classify types of buildings, are not commonly used elsewhere with the meanings applied here. Familiar terms such as “Premodern”, “Affordable”, “Postmodern” are given particular shades of meaning here, including using “affordable” as a label for subsidized housing of the 1970s and 80s. Other terms, such as “Naïve Modern” and “Designer Multiple-Dwelling” were invented to describe things we can’t find an accepted labels for but that need names in order to be able to discuss them .

2. There is a tiny cohort of buildings remaining in Manhattan that dips into the 18th century, though only barely. It includes 317 Washington Street (moved to 27 Harrison Street), 77 Bedford Street, 44 Stuyvesant Street, 273 and 279 Water Street (possibly from 1801), 18 Bowery, 191, 193, 204, 205, 206, 220, 222, 224 and 226 Front Street, 94 Greenwich Street. A list of 17th or 18th century buildings shouldn’t include (as some do) those structures (Morris Jumel Mansion, Dyckman Farmhouse) that were well outside “New-York” (as it was styled in the first half of the 19th century) when they were built and only later came within the city as it expanded to absorb them

3. Of course, some individual buildings characteristic of some periods continued to be built into the next period. The New York Central Building (1929) is a Beaux-Arts skyscraper that has every resemblance to a Premodern Early Steel-Frame Building type rather than a Prewar Setback Commercial Building, which it technically is. Conversely, some individual buildings anticipated the approaching sea changes of a new epochs can be considered precursors of their arrival. 92 Grove Street (1917) is at least ten or fifteen years ahead of its time, a Premodern Apartment House with only a lightest application of the historicist ornamentation that characterized this type. Other buildings clearly and nicely express transitions between eras by incorporating characteristics of both. Carnegie Hall Tower (1991) is a Postmodern Tower that pointed the way followed by CE Towers a decade later.

4. On another hand, wood-framed houses and tenements are very important in Brooklyn and make a critical contribution to its architectural fabric. It is striking how dissimilar the architectural fabrics of Manhattan and the outer Boroughs are, two separate species. They only overlap significantly with a minority shared types, Early and Late Brownstones, three varieties of Tenements, Prewar Apartment Houses and Postwar Apartment Buildings, Postwar Superblock Complexes, CE Towers, CE Multiple-Dwellings. Victorian Wood-framed Houses, which don’t reach critical mass in Manhattan, are very important fabric buildings in Brooklyn. Other fabric types that are extensive in the Boroughs but absent in Manhattan include, Postwar Garden Apartments, Postwar Suburban-type Houses, Late Victorian Eastlake Houses, Prewar American-type Houses, Prewar Seaside Bungalows and many more.

5. If we were in charge, such makeovers would not be permitted. Preservation and restoration is always going to pay off long-term better than counterfeiting (or so we’d like to believe). It is a rule that almost any style in almost any field is reviled by opinion in the period following. Then, inevitably, after the passing of a few decades, people look on the old style with new eyes and it finds a new appreciation and acceptance. Such might even be the case with Modern and Postmodern buildings that have undergone Current Era makeovers. If restored to their original appearance, these unfashionable creatures can become colorful artifacts of “a simpler time”.